“Move fast and break things.”

The phrase came out of Facebook’s early days and quickly became a shorthand mantra across the industry. It’s catchy, it feels daring, and it captures a mindset that values speed above all else. Whether or not it fits your context, the words still hang over a lot of engineering conversations.

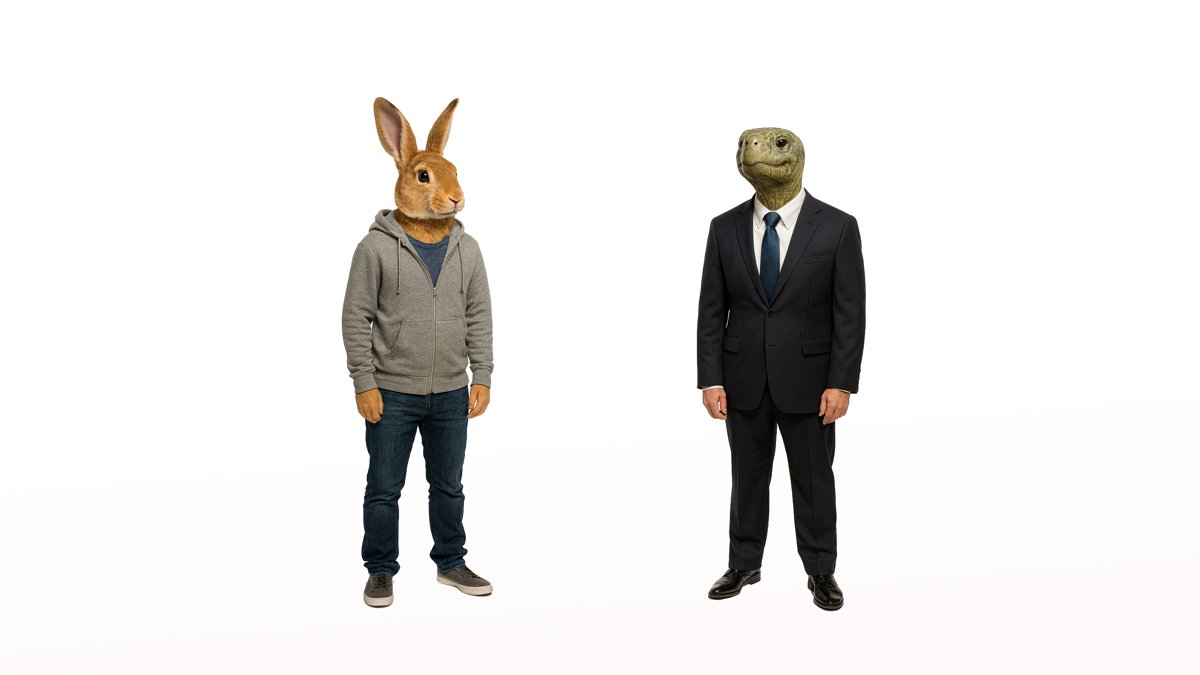

On the other end of the spectrum sits root cause culture. A culture where every failure deserves a deeper look, where learning from incidents is treated as the most valuable outcome. This is the world of blameless postmortems, of engineers digging into logs for days, of slowing down to make sure it doesn’t happen again. Most teams live somewhere in between, and that middle ground is where the real tension shows up.

A prototype can survive chaos. A consumer app can tolerate mistakes. A medical device cannot. Large organizations often talk about KTLO—keeping the lights on. It’s shorthand for the minimal cost of running a service day to day. But when a system has been built under a “move fast” approach, KTLO rarely stays minimal. Fragile deployments, poorly understood dependencies, and endless alerts eat away at teams. What looked like quick progress becomes an ongoing tax. At best it’s expensive; at worst it’s demoralizing. Rushing today often means paying tomorrow in KTLO.

The friction really shows up when companies try to move toward root cause culture without giving it any air to breathe. Retrospectives get stapled onto the sprint but deadlines don’t change. Lessons learned documents get written but priorities stay fixed. Teams are left deciding whether to apply what they’ve learned or just push the next release out the door. Over time, the ceremony becomes hollow. People stop believing that root cause work actually matters because nothing around them shifts to make it matter.

And this is why I’m writing this as part of the broader team series. As teams grow, there’s almost always a reason behind that growth. Maybe the company found traction, maybe the product is expanding, maybe the stakes are higher now than they used to be. Whatever the reason, moving along this spectrum is rarely painless. Moving fast can, by definition, help a team move fast—but only in short bursts. For a startup, that burst might mean survival. For a larger organization, it might become a slow strangle as the weight of past shortcuts piles up.

At the other end, a root cause culture can sound noble and disciplined, but it comes with its own doubts and frustrations. The military has a saying: “slow is smooth, smooth is fast.” The idea is that by taking deliberate steps, you create the conditions for speed later. There’s truth in that, but only if you actually make room for the slowness. In practice, many organizations adopt the rituals of root cause thinking without protecting the space for them to work, and end up with the worst of both worlds—neither fast, nor smooth.

If you’re in a leadership role, the simplest move you can make is to say out loud that this work is important enough to slow down for. Change a deadline. Shift a priority. Protect the space for learning. Without that, the words “root cause” will just keep echoing in postmortems while the team sprints back to break more things.